Key findings

- WeChat (the most popular chat app in China) uses two different algorithms to filter images in Moments: an OCR-based one that filters images containing sensitive text and a visual-based one that filters images that are visually similar to those on an image blacklist

- We discovered that the OCR-based algorithm has implementation details common to many OCR algorithms in that it converts images to grayscale and uses blob merging to consolidate characters

- We found that the visual-based algorithm is not based on any machine learning approach that uses high level classification of an image to determine whether it is sensitive or not; however, we found that the algorithm does possess other surprising properties

- For both the OCR- and visual-based algorithms, we uncovered multiple implementation details that informed techniques to evade the filter

- By analyzing and understanding how both the OCR- and visual-based filtering algorithms operate, we are able to discover weaknesses in both algorithms that allow one to upload images perceptually similar to those prohibited but that evade filtering

Introduction

WeChat, (Weixin 微信 in Chinese), is the dominant chat application in China and fourth largest in the world. In February 2018, WeChat reportedly hit one billion monthly active users during the Chinese Lunar New Year. The application is owned and operated by Tencent, one of China’s largest technology companies. In the past two years, WeChat has transformed beyond a commercial social media platform and become part of China’s e-governance initiatives. China’s Ministry of Public Security has been collaborating with Tencent to implement the country’s national identification card system on WeChat.

Chinese users spend a third of their mobile online time on WeChat and typically return to the app ten times a day or more. Among WeChat’s many functions, the most frequently used feature is WeChat Moments (朋友圈), which resembles Facebook’s Timeline and allows users to share images, videos, and articles. Moments has a relatively high level of intimacy, because a user’s updates on Moments can only be seen by friends who have been verified or selected by the user, and a user can only see interactions of people who are already on their WeChat contact list. Because of such perceived privacy, users reported that they frequently share details of their daily life and express personal opinions on Moments.

Operating a chat application in China requires following laws and regulations on content control and monitoring. Previous Citizen Lab research uncovered that WeChat censors content–both text and images–and demonstrates that censorship is heightened around sensitive events. Our previous work found that WeChat uses a hash-based system to filter images in one-to-one and group chats. However, image censorship on Moments is more complex: an image is filtered according to its content in a way that is tolerant to some modifications to the image.

In this report, we present our findings studying the implementation of image filtering on WeChat Moments. We found two different algorithms that WeChat Moments uses to filter images: an OCR-based one that filters images containing sensitive text and a visual-based one that filters images that are visually similar to those on an image blacklist. We found that the OCR-based algorithm has similarities to many common OCR algorithms in that it converts images to grayscale and uses blob merging to consolidate characters. We also found that the visual-based algorithm is not based on any machine learning approach that uses high level classification of an image to determine whether it is sensitive or not; however, we found that the algorithm does possess other surprising properties. By understanding how both the OCR- and visual-based algorithms work, we are able to discover weaknesses in both algorithms that allow one to upload images perceptually similar to those blacklisted but that evade filtering.

Through our findings we provide a better understanding of how image filtering is implemented on an application with over one billion users. We hope that our methods can be used as a road map for future research studying image filtering on other platforms.

Regulatory Environment in China

WeChat thrives on the huge user base it has amassed in China, but the Chinese market carries unique challenges. As Chinese social media applications continue to gain popularity, authorities have introduced tighter content controls.

Any Internet company operating in China is subject to laws and regulations that hold companies legally responsible for content on their platforms. Companies are expected to invest in staff and filtering technologies to moderate content and stay in compliance with government regulations. Failure to comply can lead to fines or revocation of operating licenses. This environment creates a system of “intermediary liability” where responsibility of content control is pushed down to companies.

In 2010, China’s State Council Information Office (SCIO) published a major government-issued document on its Internet policy. It includes a list of prohibited topics that are vaguely defined, including “disrupting social order and stability” and “damaging state honor and interests.” Control over the Internet in China has tightened since 2012 following the establishment of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). The CAC has become the new regulator of online news services replacing the SCIO. Chinese President Xi Jinping directly heads the CAC, which signals a dramatic change of the leadership’s attitudes towards Internet management: It is a matter of national security and that the (CPC) must control the Internet just as how it controls traditional media.

Recent regulations push content control liability down to the user level. In 2014, the CAC introduced regulations informally referred to as the “WeChat Ten Doctrines”, which emphasizes the implementation of a real-name registration system and a prohibition against activities that violate the “seven baselines” of observing laws and regulations, the Socialist system, the national interest, citizens’ lawful rights and interests, public order, social morality, and truthfulness of information. In 2017, the CAC released four major regulations on Internet management, ranging from strengthening real-name registration requirements on Internet forums and online comments to making individuals who host public accounts and moderate chat groups liable for content on the platforms.

Under the CAC, WeChat, along with other Chinese social media platforms, face much higher penalties than fines if they fail to moderate content. On April 9, 2018, the CAC ordered all Chinese app stores to remove the four most popular news aggregation applications for weeks because they failed to “maintain the lawful order of information sharing.” A day later, authorities demanded Toutiao, China’s top news aggregation website, and WeChat permanently shut down an account that featured parody and jokes due to “publishing vulgar and improper content.” In the same month, Tencent suspended all video playing functions on WeChat and QQ if the URL of the video was an external link.

To handle increased government pressures, companies are investing more heavily in filtering technologies and human resources to moderate content. Global Times, a Chinese state media outlet affiliated with People’s Daily, reported that tech companies are expanding their human censor team and developing artificial intelligence tools to review “trillions of posts, voice messages, photos and videos every day” to make sure their content is in line with laws and regulations. However, authorities still think that “these platforms are not fully performing their duties.”

In September 2016, Chinese authorities issued new regulations that explicitly state that messages and comments on social media products like WeChat Moments can be collected and used as “electronic data” in legal proceedings. Martin Lau Chi-ping, a senior manager at Tencent, said the following:

“We are very concerned about user data security. It is top of our concerns… In a law enforcement situation, of course, any company has to comply with the regulations and laws within the country.”

Recently, WeChat users have been arrested for “insulting police” or “threatening to blow up a government building” on Moments, which indicates that the feature may be subject to monitoring by the authorities or the company.

Previous Examples of WeChat Image Filtering

In previous Citizen Lab research, we showed that image censorship occurs in both WeChat’s chat function and WeChat Moments. Similar to keyword-based text filtering, censorship of images is only enabled for users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers. The filtering is also non-transparent in that no notice is given to a user if the image they have sent is blocked. Censorship of an image is concealed from the user who posted the censored image.

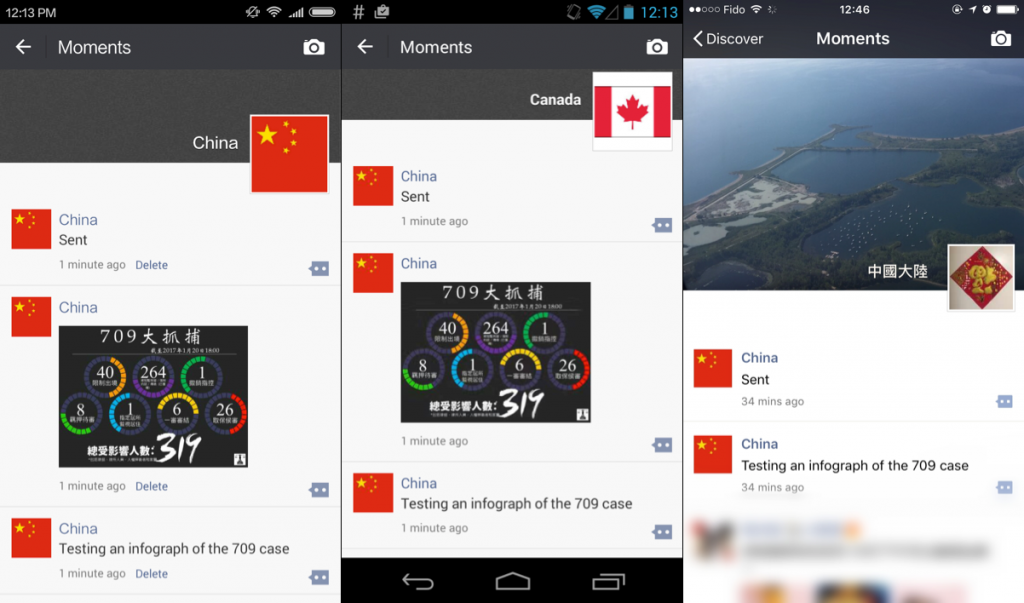

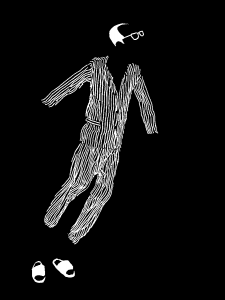

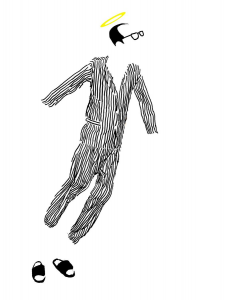

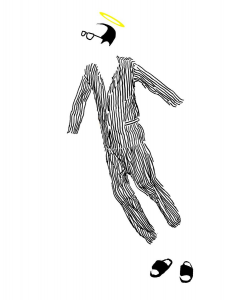

Figure 1 shows a user with an international account successfully posting a censored image: the image is visible to users with international accounts, but the post is hidden from users with China accounts.

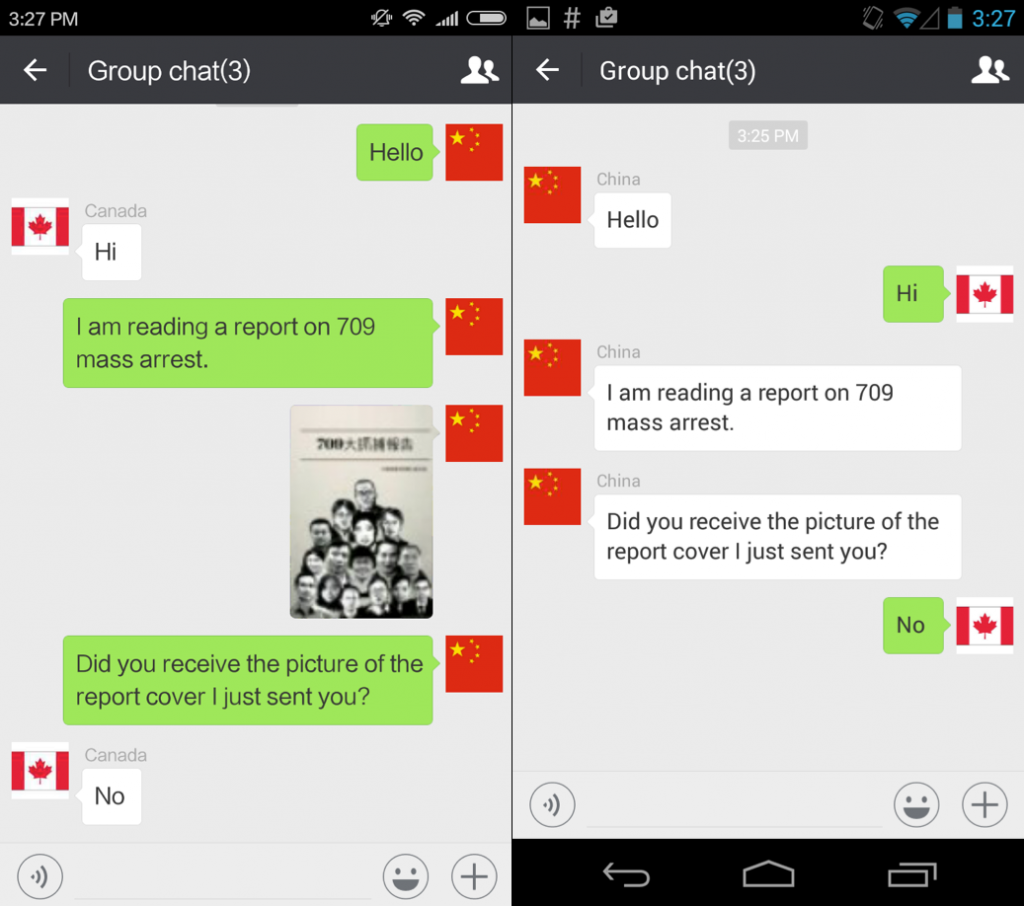

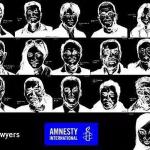

In January 2017, we discovered that a number of images related to the “709 Crackdown” (referring to a crackdown on human rights lawyers and their families in China) are blocked in group chat when using an account registered to a mainland China phone number. The censorship was found when we were performing keyword testing of news articles. When we copied and pasted the image accompanying certain news articles about the 709 Crackdown, the image itself was filtered. In subsequent sample testing, we found 58 images related to the event censored on Moments, most of which are infographics related to the 709 Crackdown, profile sketches of the affected lawyers and their relatives, or images of people holding the slogan “oppose torture, pay attention to Xie Yang” (“反对酷刑,关注谢阳”). See Figure 2 for an example of the image filtering.

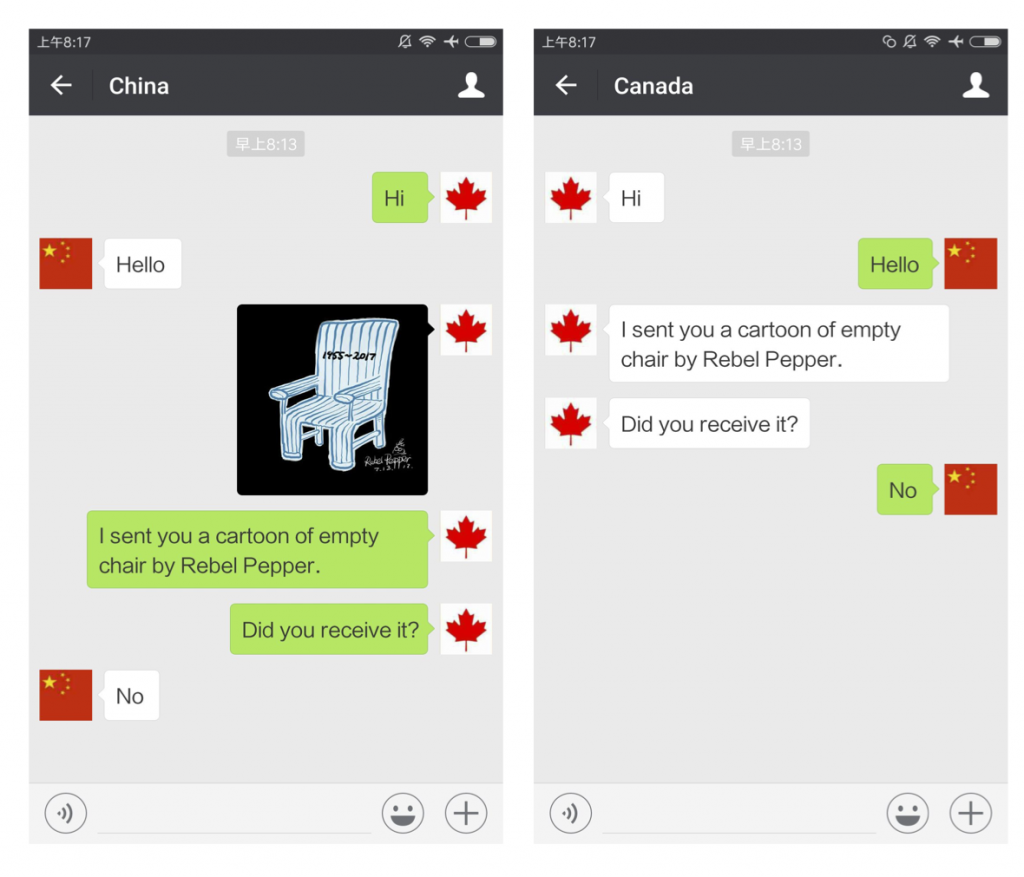

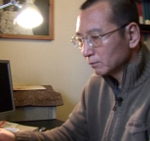

We documented similar instances of image censorship on WeChat following the death of Liu Xiaobo in July 2017. The scope of censorship was wider and more intensive compared to the case of the 709 Crackdown. Not only were images censored on WeChat’s group chat and Moments, but we also documented image filtering on WeChat’s one-to-one chat function for the first time (see Figure 3).

In the wake of Liu Xiaobo’s death, we again found that images blocked in one-to-one chat messages were also blocked on group chat and WeChat Moments. Images blocked in chat functions were always blocked on WeChat Moments. The greater attention to WeChat Moments and group chat may be due to the semi-public nature of the two features. Messages in these functions can reach a larger audience than one-to-one chat, potentially making these features subject to a higher level of scrutiny. However, the blocking of images on one-to-one chat shows an effort to restrict content across semi-public and private chat functions, demonstrating the sensitivity of Liu Xiaobo’s death.

In both cases, our tests showed that an image on Moments is filtered according to that image’s content in a way that is tolerant to some modifications to the image; however, until this study it was unclear the algorithms used by WeChat to filter and which kinds of image modifications evaded filtering and which did not. In this report, we conduct a systematic analysis of WeChat’s filtering mechanisms to understand how WeChat implements image filtering. This understanding informs weaknesses in WeChat’s algorithms and techniques for evading WeChat’s image filtering.

Analyzing Image Filtering on WeChat

We measured whether an image is automatically filtered on WeChat Moments by posting the image using an international account and measuring whether it was visible to an account registered to a mainland China phone number after 60 seconds, as we found that images automatically filtered were typically removed in 5 to 30 seconds. To determine how WeChat filters images, we performed modifications to images that were otherwise filtered and measured which modifications evaded filtering. The results of this method revealed multiple implementation details of WeChat’s filtering algorithms, and since our methods understand how WeChat’s filtering algorithm is implemented by analyzing which image modifications evade filtering, they naturally inform strategies to evade the filter.

We found that WeChat uses two different filtering mechanisms to filter images: an Optical Character Recognition (OCR)-based approach that searches images for sensitive text and a visual-based approach that visually compares an uploaded image against a list of blacklisted images. In this section we describe how testing for and understanding implementation details of both of these filtering methods led to effective evasion techniques.

OCR-based filtering

We found that one approach that Tencent uses to filter sensitive images is to use OCR technology. An OCR algorithm is an algorithm that automatically reads and extracts text from images. OCR technology is commonly used to perform tasks such as automatically converting a scanned document into editable text or to read characters off of a license plate. In this section, we describe how WeChat uses OCR technology to detect sensitive words in images.

OCR algorithms are complicated to implement and the subject of active research. While reading text comes naturally to most people, computer algorithms have to be specifically programmed and trained in how to do this. OCR algorithms have become increasingly sophisticated over the past decades to be able to effectively read text in an increasingly diverse amount of real-world cases.

We did not systematically measure how much time WeChat’s OCR algorithm required, but we found that OCR images were not filtered in real time and that after uploading an image containing sensitive text, it would typically be visible to other users between 5 and 30 seconds before it was filtered and removed from others’ views of the Moments feed.

Grayscale conversion

OCR algorithms may use different strategies to recognize text. However, at a high level, we found that WeChat’s OCR algorithm shares implementation details with other OCR algorithms. As most OCR algorithms do not operate directly on colour images, the first step they take is to convert a colour image to grayscale so that it only consists of black, white, and intermediate shades of gray, as this largely simplifies text recognition since the algorithms only need to operate on one channel.

| Algorithm | Result |

|---|---|

| Original |  |

| Average |  |

| Lightness |  |

| Luminosity |  |

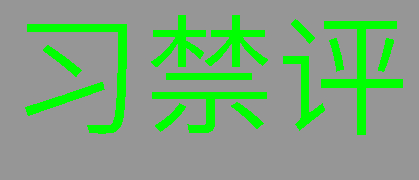

Table 1: An image with green text and a background colour of gray with the same shade as the text according to the luminosity formula for grayscale and how the text would appear to an OCR algorithm according to three different grayscale algorithms. If the OCR algorithm uses the same grayscale algorithm that we used to determine the intensity of the gray background, then the text effectively disappears to the algorithm.

To test if WeChat’s OCR filtering algorithm performed a grayscale conversion of colour images, we designed test images that would evade filtering if the OCR algorithm converted uploaded images to grayscale. We designed the images to contain text hidden in the hue of an image in such a way that it is easily legible by a person reading it in colour but such that once it is converted to grayscale, the text disappears and is invisible to the OCR algorithm. If the image evaded censorship, then the OCR algorithm must have converted the image to grayscale (see Table 1 for an illustration).

As we did not know which formula the OCR algorithm used to convert colour images to grayscale, we evaluated multiple possibilities. Coloured raster images are typically represented digitally as a two-dimensional array of pixels, each pixel having three colour channels (red, green, and blue) of variable intensity. These intensities correspond to the intensities of the red, green, and blue outputs on most electronic displays, one for each cone of the human eye.

In principle, the gray intensity of a colour pixel could be calculated according to any function of its red, green, and blue intensities. We evaluated three common algorithms:

- average(r, g, b) = (r + g + b) / 3

- lightness(r, g, b) = (max(r, g, b) + min(r, g, b)) / 2

- luminosity(r, g, b) = 0.299 r + 0.587 g + 0.114 b

To use as comparisons and to validate our technique, in addition to WeChat’s algorithm, we also performed this same analysis on two other OCR algorithms: the one provided by Tencent’s Cloud API, an online API programmers can license from Tencent to perform OCR, and Tesseract.js, a browser-based Javascript implementation of the open source Tesseract OCR engine. We chose Tencent’s Cloud OCR because we suspected it may share common implementation details with the OCR algorithm WeChat uses for filtering, and we chose Tesseract.js since it was popular and open source.

Since Tesseract.js was open source, we analyzed it first as it allowed us to look at the source code and directly observe the algorithm used for grayscale to use as a ground truth. To our surprise, the exact algorithm used was not any of the algorithms that we had initially presumed but rather a close approximation of one. Namely, it used a fixed-point approximation of the YCbCr luminosity formula equivalent to the following Javascript expression:

(255 * (77 * r + 151 * g + 28 * b) + 32768) >> 16

where “a >> b” denotes shifting a to the right by b bits, an operation mathematically equivalent to ⌊a / 2b⌋. Multiplied out, this is approximately equivalent to 0.300 r + 0.590 g + 0.109 b.

Knowing this, we created images containing filtered text in six different colours: red, (1.0, 0, 0); yellow, (1.0, 1.0, 0); green, (0, 1.0, 0); cyan, (0, 1.0, 1.0); blue, (0, 1.0, 1.0); and magenta, (1.0, 0, 1.0); where (r, g, b) is the colour in RGB colourspace and 1.0 is the highest intensity of each channel (see Table 2). These six colours were chosen because they have maximum saturation in the HSL colourspace and a simple representation in the RGB colourspace. For each colour (r, g, b), we created an image whose text was colour (r, g, b) and whose background was the gray colour (Y, Y, Y), such that Y was equal to the value of the above Javascript expression evaluated as a function of r, g, and b.

We tested the images on Tesseract.js, and any text we tried putting into the image was completely invisible to the algorithm. We found that no other grayscale algorithm consistently evaded detection on all colours, including the original luminosity formula. While very similar to the formula Tesseract.js used, it, for example, failed for the colours with a blue component, as the coefficient for the blue channel is where the formulas most disagreed. Even this small difference produced text that was detectable. Generalizing from this, we concluded that evading WeChat’s OCR filtering algorithm may prove difficult, as we may have to know the exact grayscale formula used, but once we correctly identified it, we would be able to consistently evade WeChat’s filtering algorithm with any colour of text.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|

Table 2: Each of the six colours of text tested. Here the background colour of each of the above six images was chosen according to the luminosity of the colour of that image’s text.

Knowing that our methodology was feasible as long we knew the exact algorithm that WeChat used to convert images to grayscale, we turned our attention to WeChat’s OCR algorithm. Using the same technique as before, we tested each of the three candidate grayscale conversion algorithms to determine if any would consistently evade the filter. We used the same six colours as before. For each test image, we used 25 keyword combinations randomly selected from a set that we already knew to be filtered via OCR filtering (see the Section “Filtered text content analysis” for how we created this set). For each colour (r, g, b), we used the grayscale algorithm being tested f to determine (Y, Y, Y), the colour of the gray background, where Y = f(r, g, b).

After performing this initial test, we found that only when choosing the intensity of the gray background colour as given by the luminosity formula could we consistently evade filtering for every tested colour. The other two algorithms did not evade censorship when testing most colours (see Table 3).

| Red | Yellow | Green | Cyan | Blue | Magenta | |

| Average | Evaded | Filtered | Filtered | Evaded | Filtered | Filtered |

| Lightness | Filtered | Filtered | Evaded | Filtered | Filtered | Evaded |

| Luminosity | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded |

Table 3: Results choosing the intensity of the gray background colour according to three different grayscale conversion algorithms for six different colours of text. For the average and lightness algorithms, most of the images were filtered. For the luminosity algorithm, none of them were.

We repeated this same experiment for Tencent’s online OCR platform. Unlike WeChat’s OCR filtering implementation, where we could only observe whether WeChat’s filter found sensitive text in the image, Tencent’s platform provided us with more information, including whether the OCR algorithm detected any text at all and the exact text detected. Repeating the same procedure as with WeChat, we found that again only choosing gray backgrounds according to each colour’s luminosity would consistently hide all text from Tencent’s online OCR platform. This suggested that Tencent’s OCR platform may share implementation details with WeChat, as both appear to perform grayscale conversion the same way.

To confirm that using the luminosity formula to choose the text’s background colour consistently evaded WeChat’s OCR filtering, we performed a more extensive test targeting only that algorithm. We selected five lists of 25 randomly chosen keywords we knew to be blocked. We also selected five lists of 10, 5, 2, and 1 keyword(s) chosen at random. For each of these lists, we created six images, one for each of the same six colours we used in the previous experiment. Our results were that all 150 images evaded filtering. These results show that we can consistently evade WeChat’s filtering by hiding coloured text on a gray background chosen by the luminosity of the text and that WeChat’s OCR algorithm uses the same or similar formula for grayscale conversion.

Image thresholding

After converting a coloured image to grayscale, another step in most OCR algorithms is to apply a thresholding algorithm to the grayscale image to convert each pixel, which may be some shade of gray, to either completely black or completely white such that there are no shades of gray in between. This step is often called “binarization” as it creates a binary image where each pixel is either 0 (black) or 1 (white). Like converting an image to grayscale, thresholding further simplifies the image data making it easier to process.

There are two common approaches to thresholding. One is to apply global thresholding. In this approach, a single threshold value is chosen for every pixel in the image, and if a gray pixel is less than that threshold, it is turned black, and if it is at least that threshold, it is turned white. This threshold can be a value fixed in advance, such as 0.5, a value between 0.0 (black) and 1.0 (white), but it is often determined dynamically according to the image’s contents using Otsu’s method, which determines the value of the threshold depending on the distribution of gray values in the image.

Instead of using the same global threshold for the entire message, another approach is to apply adaptive thresholding. Adaptive thresholding is a more sophisticated approach that calculates a separate threshold value for each pixel depending on the values of its nearby pixels.

To test if WeChat used a global thresholding algorithm such as Otsu’s method, we created a grayscale image with 25 random keyword combinations discovered censored via WeChat’s OCR filtering. The text was light gray (intensity 0.75) on a white (intensity 1.0) background, and the right-hand side was entirely black (intensity 0.0) (see Table 4). This image was designed so that an algorithm such as Otsu’s would pick a threshold such that all of the text would be turned entirely white.

|  |  |

|---|

Table 4: Left, the original image. Centre, what the image would look like to an OCR filter performing thresholding using Otsu’s method. Right, what the image might look like to an OCR filter performing thresholding using an adaptive thresholding technique.

We first tested the image against Tesseract.js and found that this made the text invisible to the OCR algorithm. This suggested that it used a global thresholding algorithm. Upon inspecting the source code, we found that it did use a global thresholding algorithm and that it determined the global threshold using Otsu’s method. This suggests that our technique would successfully evade OCR detection on other platforms using a global thresholding algorithm.

We then uploaded the image to WeChat and found that the image was filtered and that our strategy did not evade detection. We also uploaded it to Tencent’s Cloud OCR and found that the text was detected there as well. This suggests that these two platforms do not use global thresholding, possibly using either adaptive thresholding or no thresholding at all.

Blob merging

After thresholding, many OCR algorithms perform a step called blob merging. After the image has been thresholded, it is now binary, i.e., entirely black or white, with no intermediate shades of gray. In order to recognize each character, many OCR algorithms try to determine which blobs in an image correspond to each character. Many characters such as the English letter “i” are made up of unconnected components. In languages such as Chinese, individual characters can be made up of many unconnected components (e.g., 診). OCR algorithms use a variety of algorithms to try to combine these blobs into characters and to evaluate which combinations produce the most recognizable characters.

Figure 4: 法轮功 (Falun Gong) patterned using squares and letters.

To test whether WeChat’s OCR filtering performed blob merging, we experimented with uploading an image that could be easily read by a person but that would be difficult to read by an algorithm piecing together blobs combinatorially. To do this, we experimented with using two different patterns to fill text instead of using solid colours. Specifically, we used a tiled square pattern and a tiled letter pattern (see Table 5 and and Figure 4), both black on white. Using these patterns causes most characters to be made up of a large amount of disconnected blobs in a way that is easily readable by most people but that is difficult for OCR algorithms performing blob merging. The second pattern that tiles English letters was designed to especially confuse an OCR algorithm by tricking it into finding the letters in the tiles as opposed to the larger characters that they compose.

To test if blobs of this type affected the OCR algorithm, we created a series of test images. We selected five lists of 25 randomly chosen keyword combinations we knew to be blocked. Randomly sampling from blocked keyword combinations, we also created five lists for each of four additional list lengths, 10, 5, 2, and 1. For each of these lists, we created two images: one with the text patterned in squares and another patterned in letters.

For images with a large number of keywords, we decrease the font size to ensure that the generated images fit within a 1000×1000 pixel image. This is to ensure that images did not become too large and to ensure that they would not be downscaled, as we had previously experienced some images that were larger than 1000×1000 downscaled by WeChat, although we did not confirm that 1000×1000 was the exact cutoff. We did this to control for any effects that downscaling the images could have on our experiment such as by blurring the text.

| 1 keywords | 2 keywords | 5 keywords | 10 keywords | 25 keywords | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squares | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 | 3 / 5 |

| Letters | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 | 5 / 5 |

Table 6: The number of images that evaded filtering for each test. Letter-patterned text evaded all tests, but square-patterned did not evade two of the tests with the largest number of sensitive keywords.

Our results showed that square-patterned text evaded filtering in 92% of our tests, and letter-patterned text evaded filtering in 100% of our tests (see Table 6 for a breakdown). The reason for the two failures of squares in the 25 keyword case is not clear, but there are two possibilities. One is that the higher number of keywords per image increased the probability that at least one of those keywords would not evade filtering. The second is that images with a larger number of keywords used a smaller font size, and so there were fewer blobs per character, reducing the effectiveness of the evasion strategy. Letters were more effective in evading filtering and were perfect in our testing. This may be because of the previously suggested hypothesis that the OCR filter would be distracted by the letters in the pattern and thus miss the characters of which they collectively form, but it may also be because the letters are less dense insofar as they have fewer black pixels per white. Overall, these results suggest that WeChat’s OCR filtering algorithm considers blobs when performing text recognition and that splitting characters into blobs is an effective evasion strategy.

Figure 5: Output of Tencent Cloud OCR when uploading the Falun Gong image from Figure 4. The filter finds the constituent letters making up the characters, as well as other erroneous symbols, but not the characters 法轮功 themselves.

For comparison, we also tested these same images on Tesseract.js and Tencent’s Cloud OCR. For the former, the images always evaded detection, whereas in the latter the patterns often failed to evade detection, especially in larger images. We suspect that blobs are also important to Tencent’s Cloud OCR, but, as we found that these patterns did not evade detection only in larger images, we suspect that this is due to some processing such as downscaling that is being performed by Tencent’s Cloud OCR only on larger images. We predict that by increasing the distance between the blobs in larger images, we could once again evade filtering on Tencent’s Cloud OCR.

Character classification

Most OCR algorithms ultimately determine which characters exist in an image by performing character classification based on different features extracted from the original image such as blobs, edges, lines, or pixels. The classification is often done using machine learning methods. For instance, Tencent’s Cloud OCR advertises that it uses deep learning, and Tesseract also uses machine learning methods to classify each individual character.

In cases where deep neural networks are used to classify images, researchers have developed ways of adversarially creating images that appear to people as one thing but that trick the neural networks into classifying the image under an unrelated category; however, this work does not typically focus on OCR-related networks. One recent work was able to trick Tesseract into misreading text; however, it unfortunately required full white-box assumptions (i.e., it was done with the knowledge of all Tesseract source code and its trained machine learning models) and so their methods could not be used to create adversarial inputs for a black-box OCR filter such as WeChat’s where we do not have access to its source code or its trained machine learning models.

Outside of the context of OCR, researchers have developed black-box methods to estimate gradients of neural networks when one does not have direct access to them. This allows one to still trigger a misclassification by the neural network by uploading an adversarial image that appears to people as one thing but is classified as another unrelated thing by the neural network. While this would seem like an additional way to circumvent OCR filtering, the threat models assumed by even these black-box methods are often unrealistic. A recent work capable of working under the most restrictive assumptions assumes that an attacker has access to not only the network’s classifications, but the top n classifications and their corresponding scores. This is unfortunately still too restrictive for WeChat’s OCR, as our only signal from WeChat’s filtering is a single bit–whether the image was filtered or not. Even Tencent’s Cloud OCR, which may share implementation details with WeChat’s OCR filtering, provides a classification score for the top result but does not provide any other scores for any other potential classifications, and so the threat model is still too restrictive.

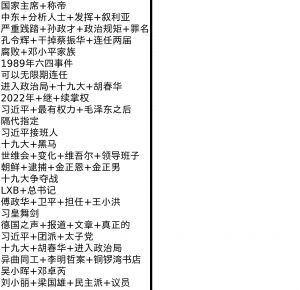

Filtered text content analysis

In this section we look at the nature of the text content triggering WeChat’s OCR-based filtering. Our previous research found that WeChat filters text chat using blacklisted keyword combinations consisting of one (e.g., “刘晓波”) or more (e.g., “六四 [+] 学生 [+] 民主运动”) keyword components, where if a message contains all components of any blacklisted keyword combination then it is filtered. We found that to implement its OCR-based image filtering WeChat also maintains a blacklist of sensitive keyword combinations but that this blacklist is different from the one used to filter text chat. Only if an image contains all components of any keyword combination blacklisted from images will it be filtered.

To help understand the scope and target of OCR-based image filtering on WeChat, in April 2018, we tested images containing keyword combinations from a sample list. This sample list was created using keyword combinations previously found blocked in WeChat’s group text chat between September 22, 2017 and March 16, 2018, excluding any keywords that were no longer blocked in group text chat at the time of our testing. These results provide a general overview of the overlap between text chat censorship and OCR-based image censorship on WeChat.

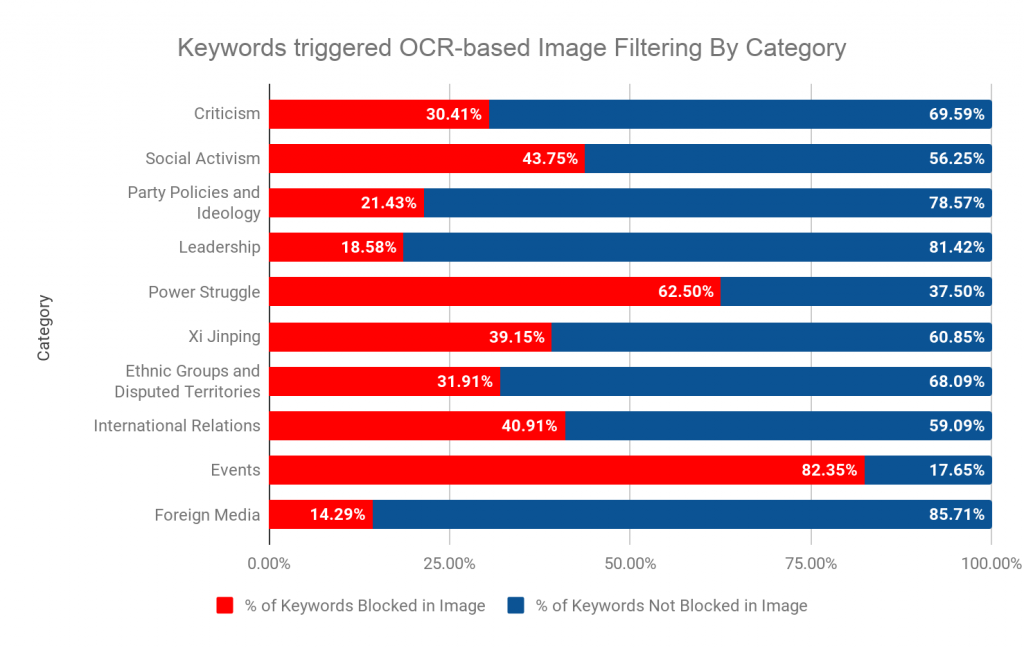

Out of the 876 keyword combinations tested, we found 309 trigger OCR-based image censorship on WeChat Moments. In previous research, we performed content analysis of keywords by manually grouping them into content categories based on contextual information. Using similar methods, we present content analysis to provide a high-level description of our keyword and image samples. Figure 6 shows the percentage of tested keyword combinations blocked and not blocked on WeChat’s OCR-based image censorship by category.

Government Criticism

We found that 59 out of 194 tested keyword combinations thematically related to government criticism triggered OCR-based image filtering. These include keyword combinations criticizing government officials and policy (see Table 7).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 中国网络沙皇 [+] 鲁 | Chinese Internet Czar [+] Lu [Wei] |

| 互联网自由 [+] 全世界 [+] 报告 [+] 最差 | Internet freedom [+] globally [+] report [+] the worst |

| 盗国贼 | kleptocrat |

Table 7: Examples of keyword combination related to government criticism that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

The first two examples make references to China’s censorship policies: Lu Wei, the former head of the Cyberspace Administration of China (the country’s top-level Internet management office), is often described as China’s “Internet czar”; and in 2017, Freedom House ranked China as “the world’s worst abuser of Internet freedom” for the third year in a row. The keyword ( “盗国贼” kleptocrat) is an derogatory reference to Wang Qishan, the current Vice President of China whose family has allegedly benefited from ties to Chinese conglomerate HNA group.

|  |  |

|---|

Table 8: An example of OCR-based image filtering in WeChat Moments. A user with an international account (on the right) posts an image containing the text “互联网自由 全世界 报告 最差” (Internet freedom [+] globally [+] report [+] the worst), which is hidden from the Moments’ feed of user with China account (in the middle). The image is visible in the user’s own feed as well as to another international account (on the left).

Party Policies and Ideology

In previous work, we found that even keyword combinations that were non-critical and that only made neutral references to CPC ideologies and central policy were blocked on WeChat. Eighteen out of 84 tested keywords made neutral references to CPC policies and triggered OCR-based image filtering (see Table 9).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 信用评分 [+] 大数据 [+] 社交媒体 [+] 社会信用体系 | credit score [+] big data [+] social media [+] Social Credit System |

| 党的建设 [+] 全国高校 [+] 工作会议 [+] 思想政治 | party building [+] colleagues nationwide [+] work meetings [+] thought politics |

Table 9: Examples of keyword combinations related to Party policies and ideology that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Social Activism

Forty-eight keyword combinations in our sample set include references to protest, petition, or activist groups. We found that 21 of them triggered OCR-based image filtering (see Table 10).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 公开信 [+] 起义 | open letter [+] uprising |

| 纪念晓波 | commemorate [Liu] Xiaobo |

Table 10: Examples of keyword combinations related to social activism that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Leadership

Past work shows that direct or indirect references to the name of a Party or government leader often trigger censorship. We found that among the 113 tested keyword combinations that made general references to government leadership, 21 triggered OCR-based image filtering (see Table 11). For example, we found that both the simplified and traditional Chinese version of “Premier Wang Qishan” triggered OCR-based image filtering. Around the 19th National Communist Party Congress in late 2017, there was widespread speculation centering on whether Wang Qishan, a close ally of Xi, would assume the role of Chinese premier.

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 王岐山总理 | Premier Wang Qishan (in simplified Chinese characters) |

| 王岐山總理 | Premier Wang Qishan (in traditional Chinese characters) |

Table 11: Examples of keyword combination related to leadership that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Xi Jinping

Censorship related to President Xi Jinping has increased in recent years on Chinese social media. The focus of censorship related to Xi warrants testing it as a single category. Among the 258 Xi Jinping-related keyword tested, 101 triggered OCR-based image censorship (see Table 12). Keywords included memes that subtly reference Xi (such as likening his appearance to Winnie the Pooh), and derogatory homonyms (吸精瓶, which literally means Semen sucking bottle).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 中共总书记 [+] 习近平连任 | General Secretary of CPC [+] Xi Jinping wins another term |

| 维尼 [+] 领导人 | Winnie [the Pooh] [+] leader |

| 吸精瓶 | Semen sucking bottle |

Table 12: Examples of keyword combinations related to Xi Jinping that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Power Struggle

Content in this category is thematically linked to power struggles or personnel transition within the CPC. Smooth power transition has been a challenge through the CPC’s history. Rather than institutionalizing the process, personnel transitions are often influenced by patronage networks based on family ties, personal contacts, and where individuals work. We found that 40 of the 64 tested keywords in this content category triggered OCR-based image filtering (see Table 13).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 十九大 [+] 團派 [+] 江派 | 19th Party Congress [+] [Youth] League clique |

| 党内 [+] 权力斗争 [+] 薄熙来 | intra-party [+] power struggle [+] Bo Xilai |

Table 13: Examples of keyword combinations related to power struggle that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

International Relations

Forty-four keywords in our sample set include references to China’s relations with other countries. We found 18 of them triggered OCR-based image filtering (see Table 14).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 争议 [+] 安倍晋三 [+] 岛屿 [+] 日本 | dispute [+] Shinzo Abe [+] island [+] Japan |

| 丹麦女王 [+] 大熊猫 [+] 玛格丽特 [+] 访华 | Denmark Queen [+] big panda [+] Margaret [+] visit China |

Table 14: Examples of keyword combinations related to international relations that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Ethnic Groups and Disputed Territories

Content in this category includes references to Hong Kong, Taiwan, or ethnic groups such as Tibetans and Uyghurs. These issues have long been contested and are frequently censored topics in mainland China. We found 15 out of 47 keywords tested in this category triggered OCR-based image censorship (see Table 15).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 公投 [+] 台湾 [+] 独立国家 | referendum [+] Taiwan [+] independent country |

| 中国政府 [+] 加强 [+] 新疆 [+] 维吾尔人 | Chinese government [+] strengthen [+] Xinjiang [+] Uyghurs |

Table 15: Examples of keyword combinations related to ethnic groups and disputed territories that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

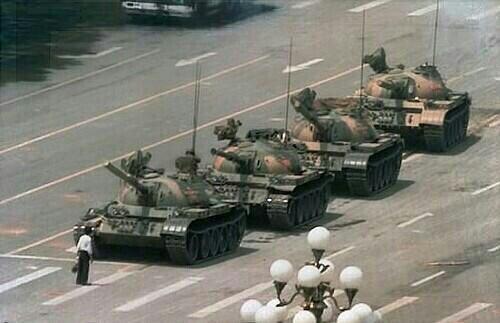

Events

Content in this category references specific events such as the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square protest. We found that 14 of the 17 tested event-related keywords triggered OCR-based image filtering (see Table 16). Thirteen of the keywords were related to the Tiananmen Square protests. We also found references to more obscure events censored such as the suicide of WePhone app founder Sun Xiangmao, who said his ex-wife Zhai Xinxin had blackmailed him into paying her 10 million RMB. Although the event attracted wide public attention and online debates, it is unclear why the keyword was blocked.

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 1989 [+] 民主运动 | 1989 [+] democracy movement |

| 坟头蹦迪 [+] 携程 [+] 翟欣欣 | dancing at one’s buried place [+] Ctrip [+] Zhai Xinxin |

Table 16: Examples of keyword combinations related to events that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Foreign Media

The Chinese government maintains tight control over news media, especially those owned and operated by foreign organizations. We found one out of three blocked text-based images that include names of news organizations that operate outside of China and publish critical reports on political issues (see Table 17).

| Keyword combination | Translation |

|---|---|

| 德国之声 [+] 报道 [+] 文章 [+] 真正的 | Deutsche Welle [+] Report [+] Article [+] True |

Table 17: Example of keyword combinations related to foreign media that triggered OCR-based image filtering.

Visual-based filtering

In the previous section we analyzed how WeChat filters images containing sensitive text. In this section we analyze the other mechanism we found that WeChat uses to filter images: a visual-based algorithm that can filter images that do not necessarily contain text. This algorithm works by comparing an image’s similarity to those on a list of blacklisted images. To test different hypotheses concerning how the filter operated, we performed modifications to sensitive images that were normally censored and observed which types of modifications evaded the filtering and which did not, allowing us to evaluate whether our hypotheses were consistent with our observed filtering.

Like with WeChat’s OCR-based filtering, we did not systematically measure how much time WeChat’s visual-based filtering required. However, we found that after uploading a filtered image that does not contain sensitive text, it would typically be visible to other users for only up to 10 seconds before it was filtered and removed from others’ views of the feed. This may be because they were either filtered before they were made visible or after they were visible but before we could refresh the feed to view them. Since this algorithm typically takes less time than the OCR-based one, this algorithm would appear to be less computationally expensive than the one used for OCR filtering.

Grayscale conversion

We performed an analysis of their grayscale conversion algorithm similar to the one we performed when evaluating WeChat’s OCR filtering to determine which grayscale conversion algorithm, if any, the blacklist-based image filtering was using. Like when testing the OCR filtering algorithm, we designed experiments such that if the blacklisted image filtering algorithm uses the same grayscale algorithm that we used to determine the intensity of gray in the image, then the image effectively disappears to the algorithm and evades filtering.

|  |

|---|

Table 18: Left, the original sensitive image. Right, the image thresholded to black and white, which is still filtered.

We chose an image originally containing a small number of colours and that we verified would still be filtered after converting to black and white (see Table 18). We used the black and white image as a basis for our grayscale conversion tests, where for each image we would replace white pixels with the colour to test and black with that colour’s shade of gray according to the grayscale conversion algorithm we are testing (see Table 19). As before, we tested three different grayscale conversion algorithms: Average, Lightness, and Luminosity (see the section on OCR filtering for their definitions).

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|

Table 19: Each of the six colours tested. Here the intensity of the gray background of each image was chosen according to the luminosity of the foreground colour.

| Red | Yellow | Green | Cyan | Blue | Magenta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Evaded | Filtered | Filtered | Evaded | Filtered | Filtered |

| Lightness | Filtered | Filtered | Filtered | Filtered | Filtered | Filtered |

| Luminosity | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded |

Table 20: Results choosing the intensity of the gray background according to three different grayscale conversion algorithms for six different colours of text. Only when using the luminosity algorithm were no images were filtered.

We found that the results are largely consistent with those previously found when testing the OCR algorithm suggesting that both the OCR-based and the visual-based algorithms use the same grayscale conversion algorithm. In both cases, most images created according to the Average and Lightness algorithms were filtered, whereas all images created according to the Luminosity algorithms evaded filtering (see Table 20). This suggests that WeChat’s blacklisted image filtering, like their OCR-based image filter, converts images to grayscale and does so using the Luminosity formula.

Cryptographic hashes

A simple way to compare whether two images are the same is by either hashing their encoded file contents or the values of their pixels using a cryptographic hash such as MD5. While this makes image comparison very efficient, this method is not tolerant of even small changes in values to pixels, as cryptographic hashes are designed such that small changes to the hashed content result in large changes to the hash. This inflexibility is incompatible with the kinds of image modifications that we found the filter tolerant of throughout this report.

Machine learning classification

We discussed in the OCR section about how machine learning methods, including neural networks and deep learning, can be used to identify the text in an image. In this case, the machine learning algorithms classify each character into a category, where the different categories might be a, b, c, …, 1, 2, 3, …, as well as Chinese characters, punctuation, etc. However, machine learning can also be used to classify more general purposes images into high level categories based on their content such as “cat” or “dog.” For purposes of image filtering, many social media platforms use machine learning to classify whether content is pornography.

If Tencent chose to use a machine learning classification approach, they could attempt to train a network to recognize whether an image may lead to government reprimands. However, training a network against such a nebulous and nuanced category would be rather difficult considering the vagueness and fluidity of Chinese content regulations. Instead, they might identify certain more well-defined categories of images that would be potentially sensitive, such as images of Falun Gong practitioners or of deceased Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, and then classify whether images belong to these sensitive categories.

Tencent advertises YouTu, an API developed by the company’s machine learning research team, for providing “artificial intelligence-backed solution to online content review.” Tencent claims that the API is equipped with image recognition functions, including OCR and facial recognition technologies, and is able to detect user generated images that contain “pornographic, terrorist, political, and spammy content”. In the case of terrorism-related images, YouTu provides specific categories of what it considers sensitive: militants (武装分子), controlled knives and tools (管制刀具), guns (枪支), bloody scenes (血腥), fire (火灾), public congregations (人群聚集), and extremism and religious symbols or flags (极端主义和宗教标志、旗帜) (see Table 21). To test if WeChat uses this system, we tested the sample images that Tencent provided on their website advertising the API (see Table 22). We found none of them to be censored.

|  |

|---|

Table 22: Left, the original image of knives, which Tencent’s Cloud API classifies as “knives” with 98% confidence. Right, the mirrored image of knives, which the Cloud API classifies as “knives” with 99% confidence. Mirroring the image had virtually no effect on the Tencent classifier’s confidence of the image’s category and no effect on the ultimate classification.

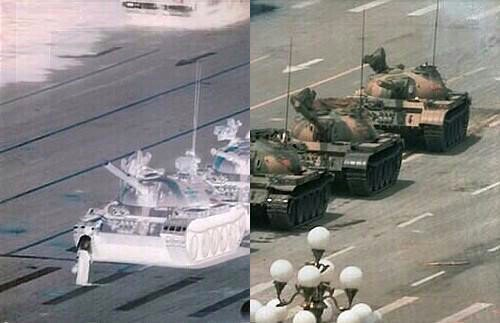

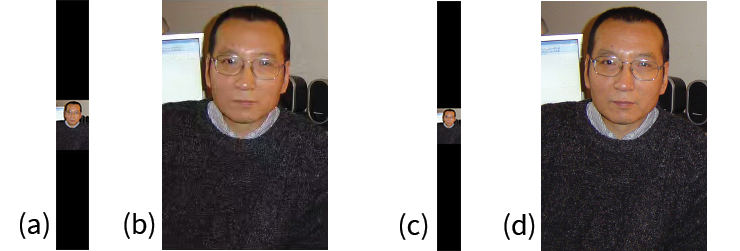

After these results, we wanted to test more broadly as to whether they may be using any sort of machine learning classification system at all or whether they were maintaining a blacklist of specific sensitive images. To do this, we performed a test that would modify images that we knew to be filtered in a way that semantically preserved their content while nevertheless largely moving around their pixels. We decided to test mirroring (i.e., horizontally flipping) images. First, as a control case, we submitted the mirrored images of each of the seven categories from Table 21. We found that, as we expected, mirroring the images did not affect what they were classified as by Tencent’s Cloud API (see Table 22 for an example).

|  |

|---|

Table 24: Left, the 15th image we tested, an image of Liu Xiaobo. Right, the mirrored image. Although the images technically have pixels in different positions, they both show a depiction of the deceased Liu Xiaobo, but only the original image on the left is filtered.

Next, we mirrored 15 images that we found to be filtered using data from previous reports and other contextual knowledge. Upon uploading them to WeChat, we found that none of them were filtered after mirroring. Other semantic-preserving operations such as cropping the whitespace from the image in Table 24 also allowed the image to evade filtering. These results, as well as additional results described further below, strongly suggest that no sort of high level machine learning classification system is being used to trigger the observed filtering on WeChat. Rather, these results suggest that there is a specific blacklist of images being maintained by Tencent that each image uploaded is somehow being compared against using some kind of similarity metric. This type of approach may be desirable as it easily allows Tencent to censor specific sensitive images that may be trending or that they are otherwise asked to censor by a government official regardless of the topic or category of the image. Note that this does not rule out the use of machine learning methods all together. Rather, this rules out any sort of filtering based on high level image classification.

Invariant features

There are different ways of describing images in a way that are invariant to certain transformations such as translation (e.g., moving the position of an image on a blank canvas), scale (e.g., downscaling or upscaling an image preserving its aspect ratio), and rotation (e.g., turning an image 90 degrees onto its side). For instance, Hu moments are a way of describing an image using seven numbers that are invariant to translation, scale, and rotation. For example, you could rotate an image and make it twice as large, and if you calculated the resulting image’s Hu moments they would be the nearly the same as those of the original (for infinite resolution images they are exactly the same, but for discrete images with finite resolution, the numbers would be approximately equal). Zernike moments are similar to Hu moments except that they are designed such that one can calculate an arbitrarily high number of them in order to generate an increasingly detailed description of the image.

Hu and Zernike moments are called global features because each moment describes an entire image; however, there also exist local feature descriptors to only describe a specific point in an image. By using local feature descriptors to describe an image, one can more precisely describe the relevant parts of an image. The locations of these descriptors are often chosen through a separate keypoint-finding process designed to find the most “interesting” points in the image. Popular descriptors such as SIFT descriptors are, like Hu and Zernike moments, invariant to scale and rotation.

To test if WeChat uses global or local features with these invariance properties to compare similarity between images, we tested if the WeChat image filter is invariant to the same properties as these features. We trivially knew that WeChat’s algorithm was invariant to scale as we had quickly found that any size of an image not trivially small would be filtered (in fact there was no reason to think that we were ever uploading an image the same size as the one on the blacklist). To test rotation, we rotated each image by 90 degrees counterclockwise. After testing these rotations on the same 15 sensitive images we tested in the previous section, we found that all consistently evaded filtering. This suggests that whatever similarity metric WeChat uses to compare uploaded images to those in a blacklist is not invariant to rotation.

Intensity-based similarity

Another way to compare similarity between two images is to treat each as a one-dimensional array of pixel intensities and then compare these arrays using a similarity metric. Here we investigate three intensity-based similarity metrics: the mean absolute difference, statistical correlation, and mutual information.

Mean absolute difference

One intensity-based method to compare similarity between two images is to compare the mean absolute difference of their pixel intensities. This is to say, for each pixel, subtract from its intensity the intensity of the corresponding pixel in the other image and then take its absolute value. The average of all of these absolute differences is the images’ mean absolute difference. Thus, values close to zero represent images that are very similar.

To determine if this was the similarity metric that WeChat used to compare images, we performed the following experiment. We inverted, or took the negative, of each of our 15 images and measured whether the inverted image was still filtered. This transformation was chosen since it would produce images that visually resemble the original image while producing a mean absolute difference similar to that of an unrelated image.

|  |  |  |

|---|

Table 25: Out of 15 images, these four evaded filtering. Compared to their non-inverted selves, they had mean absolute differences of 0.87, 0.66, 0.85, and 0.67, respectively.

We found that out of the 15 images we tested, only four of their inverted forms evaded filtering (see Table 25). The evaded images had an average mean absolute difference of 0.76, whereas the filtered ones had an average of 0.72. Among the inverted images that evaded filtering, the lowest mean absolute difference was 0.55, whereas among the inverted images that were filtered, the highest mean absolute difference was 0.97. This suggests that image modifications with low mean absolute differences can still evade filtering, whereas images with high mean absolute differences can still be filtered. Thus it would seem that mean absolute difference is not the similarity metric being used.

Statistical correlation

Another intensity-based approach to comparing images is to calculate their statistical correlation. The correlation between both images is the statistical correlation between each of their pixel intensities. The result is a value between -1 and 1, where a value close to 1 signifies that the brighter pixels in one image tend to be the brighter pixels in the other, and a value close to 0 signifies little correlation. Values close to -1 signify that the brighter pixels in one image tend to be the darker pixels in the other (and vice versa), such as if one image is the other with its colours inverted. As this would suggest that the images are related, images with a correlation close to both -1 and 1 can be considered similar.

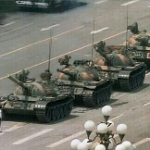

Figure 7: Left, the original image. Right, the same image with the colours on the left half on the image inverted. When converted to grayscale, these images have a nearly zero correlation of -0.02, yet the image on the right is still filtered.

To test whether image correlation is used to compare images, we created a specially crafted image by inverting the colours of the left half on the image while leaving the colours in the right half unchanged (see Figure 7). By doing this, the left halves would have strong negative correlation, and the right halves would have strong positive correlation, and so the total correlation would be around zero. We found that our image created this way had a near zero correlation of -0.02, yet it was still filtered. This suggests that statistical correlation between images is not used to determine their similarity.

Mutual information

A third intensity-based approach to compare images is to calculate their mutual information. A measurement of mutual information called normalized mutual information (NMI) may be used to constrain the result to be between 0 and 1. Intuitively, mutual information between two images is the amount of information that knowing the colour of a pixel in one image gives you about knowing the colour of a pixel in the same position in other image (or vice versa).

Similar to when we were testing image correlation, we wanted to produce an image that has near-zero NMI but is still filtered. We found that the image that is half-inverted unfortunately still has a NMI of 0.89, a very high number. This is because knowing the colour of a pixel in the original image still gives us a lot of information about what colour it will be in the modified one, as in this case it will be either the original colour or its inverse. In this metric, the distance between colours is never considered, and so there is no longer a cancelling out effect.

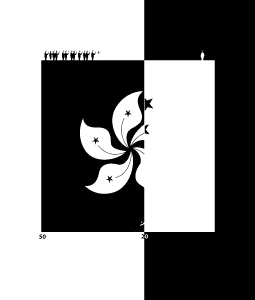

Figure 8: Left, the original image in grayscale. Right, the image converted to black and white and inverted to the right of the flag transition. Although these images have a near-zero NMI of 0.03, the image on the right is still filtered.

To create an image with low NMI compared to its original, we took a sensitive image that used colours fairly symmetrically and converted it to black and white. We then inverted nearly half of the image (see Figure 8). Since the modified image is in black and white, knowing the colour of a pixel in the original now gives you little information about the colour in the other image, as most colours appear equally on both sides of the image; it is just as likely to be either its colour or its inverse, and since there are only two colours used in the modified image, knowing that does not provide any information.

Note that in our modified image, we did not split the original image with its inverse image exactly down the middle as we did with the Tank Man photo in Figure 7. We had originally tried this but found that it was not filtered. However, when we split it along the natural border between the Hong Kong and Chinese flags in the image, then it was filtered. This result suggested that edges may be an important feature in WeChat’s algorithm.

Histogram similarity

Another general method of comparing images is according to normalized histograms of their pixel intensities. Binning would typically be used to allow for similar colours to fall into the same bins. A simple way of comparing images is to take a histogram over each image in its entirety. This similarity metric would reveal if two images use similar colours, but since it does not consider the locations of any of the pixels, it lacks descriptive power when used as a similarity metric. As such, it would be invariant to rotation. However, as we saw in the earlier section, Tencent’s filter is not. This algorithm would also be invariant to non-uniform changes in scale, (i.e., changes in aspect ratio). To test if WeChat’s filtering algorithm is, we changed the aspect ratio of the same 15 sensitive images we tested in the previous section, in one set reducing each image’s height to 70%, and in another reducing each image’s width to 70%. We found that in all but one case (an image that had its width reduced by 70%) the new images evaded filtering. This further suggests that WeChat is not using a simple histogram approach.

A histogram-based approach would also be sensitive to changes in image brightness and inverting an image’s colours. However, we experimented with increasing images brightness by 0.4 (i.e., increasing each of the R, G, and B values for each pixel by 0.4) or inverting their colours. In each case, the image was still filtered. Since a histogram-based metric would be sensitive to these transformations, this is unlikely to be Tencent’s similarity metric.

One enhancement to the histogram approach is to use a spatial histogram, where an image is divided into regions and a separate histogram is counted for each region. This would allow the histogram to account for the spatial qualities of each image. We found reference to Tencent using such an algorithm in a June 2016 document on Intel’s website describing optimizations made to Tencent’s image censorship system. The document is titled “Tencent Optimizes an Illegal Image Filtering System.” The document describes how Intel worked with Tencent to use SIMD technology, namely Intel’s SSE instruction set to improve the performance of Tencent’s filtering algorithm used on WeChat and other platforms to censor images. The document does not reveal the exact algorithm used. However, it does include a high level outline and some code samples that reveal characteristics of the algorithm.

The high level view of the algorithm described in the document is as follows.

- First, an uploaded image is decoded.

- Next, it is then smoothed and resized to a fixed size.

- A fingerprint of the image is calculated.

- The fingerprint is compared to the fingerprint of each illegal image. If the image is determined to be illegal, then it is filtered.

The details of the fingerprinting step are never explicitly described in the document, but from what we can infer from code samples, we suspect that they were using the following fingerprinting algorithm:

- The image is converted to grayscale.

- The image is then divided into a 3×3 grid of equally sized rectangle regions.

- For each of the 9 regions, a 4-bin histogram is generated by counting and binning based on the intensity of each pixel in that region. The fingerprint is a vector of these 9 × 4 = 36 counts.

|  |  |

|---|

Table 26: Left, the original filtered image. Centre, the original image with the contrast drastically decreased. Right, the original image with the colours inverted. Both the low contrast and inverted images are filtered.

It is never explicitly stated in the report, but file names referenced in the report (simhash.cpp, simhash11.cpp) would suggest that the SimHash algorithm may be used to reduce the size of the final fingerprint vector and to binary-encode it. This spatial-histogram-based fingerprinting algorithm is, however, also inconsistent with our observations. While this approach would explain why the metric is not invariant to mirroring or rotation, it still would be sensitive to changes in contrast or to inverting the colours of the image, which we found WeChat’s algorithm to be largely robust to (see Table 26 for an example of decreased contrast and inverted colours).

Figure 9: Original image.

Figure 10: Image modified such that each of the nine regions has been vertically flipped.

In light of finding Intel’s report, we decided to perform one additional test. We took a censored image and divided it into nine equally sized regions as done in the fingerprinting algorithm referenced in Intel’s report. Next, we independently vertically flipped the contents of each region (see Figures 9 and 10). The contents of each region should still have the same distribution of pixel intensities, thus matching the fingerprint; however, we found that the modified image evaded filtering. It is possible that Tencent has changed their implementation since Intel’s report.

Edge detection

Edges are often used to compare image similarity. Intuitively, edges represent the boundaries of objects and of other features in images.

|  |  |

|---|

Table 27: Two kinds of filtering. Left, the original image. Centre, the image with a Sobel filter applied. Right, the Canny edge detection algorithm.

There are generally two approaches to edge detection. The first approach involves taking the differences between adjacent pixels. The Sobel filter is a common example of this (see Table 27). One weakness of this approach is that by signifying small differences as low intensity and larger differences as high intensity, it still does not specify in a 0-or-1 sense which are the “real” edges and which are not. A different approach is to use a technique like Canny edge detection which uses a number of filtering and heuristic techniques to reduce each pixel of a Sobel-filtered image to either black (no edge) or white (an edge is present). As this reduces each pixel to one bit, it is more computationally efficient to use as an image feature.

There is some reason to think that WeChat’s filtering may incorporate edge detection. When we searched online patents for references to how Tencent may have implemented their image filtering, we found that in June 2008 Tencent filed a patent in China called 图片检测系统及方法 (System and method for detecting a picture). In it they describe the following real-time system for detecting blacklisted images after being uploaded.

- First, an uploaded image is resized to a preset size in a way that preserves aspect ratio.

- Next, the Canny edge detection algorithm is then used to find the edges in the uploaded image.

- A fingerprint of the image is calculated.

- First, the moment invariants of the result of the Canny edge detection algorithm are calculated. It is unclear what kind of moment invariants are calculated.

- In a way that is not clearly specified by the patent, the moment invariants are through some process binary-encoded.

- Finally, the resulting binary-encoded values are MD5 hashed. This resulting hash is the image fingerprint.

- fingerprint of the uploaded image is then compared to the fingerprint of each illegal image. If the fingerprint matches any of those in the image blacklist, then it is filtered.

Steps 1 and 4 are generally consistent with our observations in this report thus far. Uploaded images are resized to a preset size in a way that preserves aspect ratio, and the calculated fingerprint of an image is compared to those in a blacklist.

In step 3, the possibility of using Canny edge detection is thus far compatible with all of our findings in this report (although it is far from being the only possibility). The use of moment invariants is not strongly supported, as WeChat’s filtering algorithm is very sensitive to rotation. Moreover, encoding the invariants into an MD5 hash through any imaginable means would seem inconsistent with our observations thus far, as MD5, being a cryptographic hash, has the property that the smallest of changes to the hashed content have, in expectation, an equal size of effect on the value of the hash as that of the largest changes. However, we might imagine that they use an alternative hash such as SimHash, which can hash vectors of real-valued numbers such that two hashes can be compared for similarity in a way that approximates the original cosine similarity between the hashed vectors.

We found that designing experiments to test for the use of Canny edge detection difficult. The algorithm is highly parameterized, and the parameters are often determined dynamically using heuristics based on the contents of an image. Moreover, unlike many image transformations such as grayscale conversion, Canny edge detection is not idempotent, (i.e., the canny edge detection of a canny edge detection is not the same as the original canny edge detection). This means that we cannot simply upload an edge-detected image and see if it gets filtered. Instead, we created test images by removing as many potentially relevant features of an image as possible while preserving the edges of an image.

|  |

|---|

Table 28: Left, the original filtered image. Right, the image thresholded according to Otsu’s method, which is also filtered.

To do this, we again returned to thresholding, which we originally explored when analyzing the WeChat filter’s ability to perform OCR. By using thresholding, we reduced all pixels to either black or white, eliminating any gray or gradients from the image, while hopefully largely preserving the edges in the image (see Table 28).

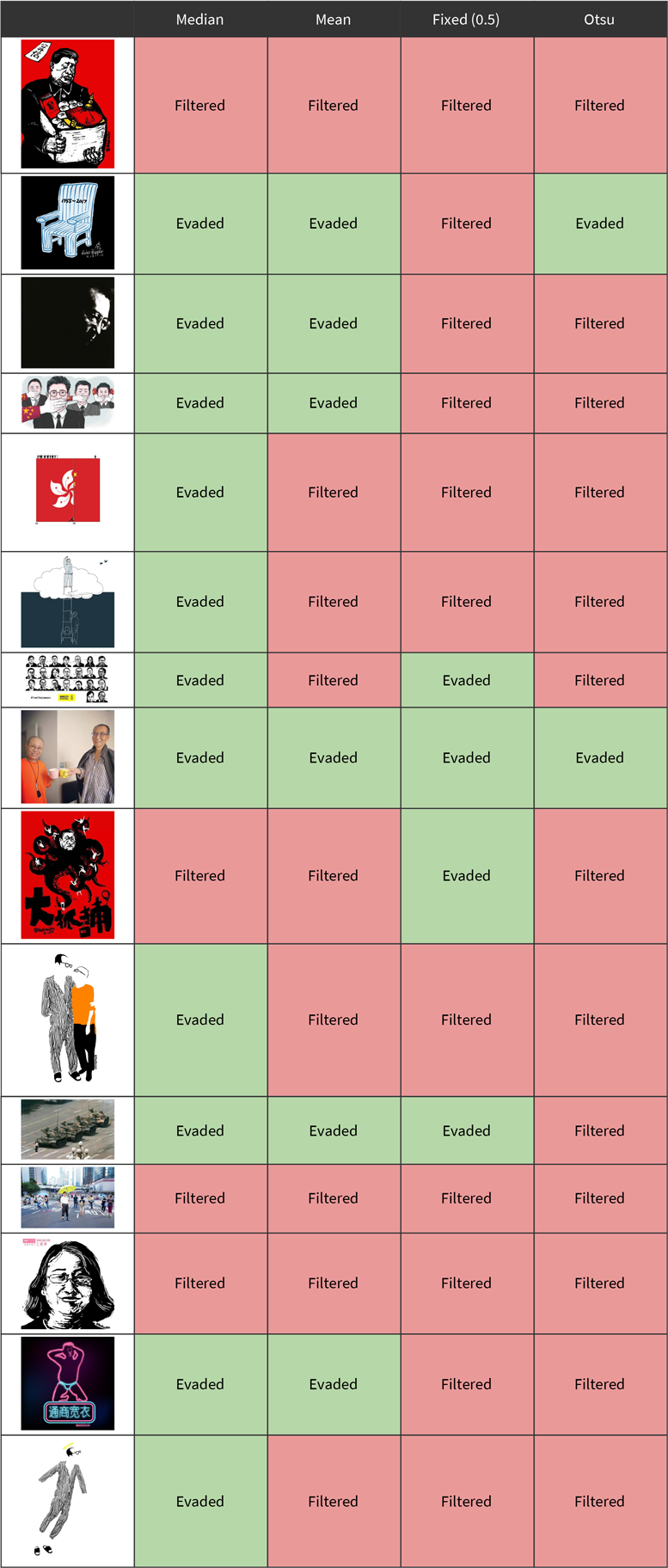

In our experiment, we wanted to know what effects performing thresholding would have on images that we knew were filtered. To do this, on our usual 15 images we applied global thresholding according to four different thresholds: the image’s median grayscale pixel value, the image’s mean grayscale pixel value, a fixed value of 0.5, and a threshold value chosen using Otsu’s method (see Table 29).

We found that all but one image was still filtered after being thresholded by at least one of the four algorithms.

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) |

Table 30: (a), Liu Xiaobo’s empty chair, when thresholded according to Otsu’s method, its stripes are lost. (b), Liu Xiaobo and his wife thresholded according to Otsu’s method with the algorithm performing poorly on the gradient background. (c) and (d), an artificially created gradient background and its thresholded counterpart. In (d), an edge has been created where perceptually one would not be thought to exist.

All but two of the images were still filtered after being thresholded using a threshold determined via Otsu’s method. Among the two images that were not filtered, one was the image of Liu Xiaobo’s empty chair. This may be because the threshold chosen by Otsu’s method did not distinguish the stripes on the empty chair. The other was the photograph of Liu Xiaobo and his wife clanging coffee cups. This may be because thresholding does not preserve edges well with backgrounds with gradients, as the thresholding will create an erroneous edge where none actually exists (see Table 30).

As an additional test, we took the 15 images thresholded using Otsu’s method and inverted them. This would preserve the location of all edges while radically altering the intensity of many pixels.

We found that among the 13 images that were filtered after applying Otsu’s method, only four were filtered after they were additionally inverted (see Table 31). The two images that were not filtered before were also not filtered after being inverted. This suggests that, if edge detection is used, it is either in addition to other features of the image, or the edge detection algorithm is not one such as the Canny edge detection algorithm which only tracks edges not their “sign” (i.e., whether the edge is going from lighter to darker versus darker to lighter).

Between the Intel report and the Tencent patent, we have seen external evidence that WeChat is using either spatial histograms or Canny edge detection to fingerprint sensitive images. Since neither seems to be used by itself, is it possible that they are building a fingerprint using both? To test this, we took the 13 filtered images thresholded using Otsu’s method and tested to see how light we could lighten the black channel such that the thresholded image is still filtered.

20

|

215

|

56

|

11

|

12

|

19

|

15

|

18 18 |

28

|

55

|

255

|

21

|

18

|

Table 32: The lightest image still filtered, and, below each image, the difference in intensities between white and the darkest value (out of 255).

Our results show that sometimes the difference in intensities can be small for an image to still be filtered and that sometimes it must be large, with one case allowing no lightening of the black pixels at all (see Table 32). The images with small differences are generally the non-photographic ones with well-defined edges. These are images where the thresholding algorithm would have been most likely to preserve features of the image such as the edges in the first place. Thus, they are more likely to preserve these features when they have been lightened up, especially after possible filtering such as downscaling has been applied.

Nevertheless, this result shows that the original image need not have a similar spatial histogram. Six of the seven images in Table 32 have an intensity difference of less than 64, which, in the 4-binned spatial histogram algorithm referenced in the Intel report, would put every pixel into the same bin. When we repeat this experiment with the inverted thresholded images and lightening them such that every pixel fit into the same bin, we could not get any additional inverted images to be filtered, despite these images preserving the locations of the edges and having the same spatial histograms as images that we knew to be filtered. All together this suggests that spatial histograms are not an important feature of these images.

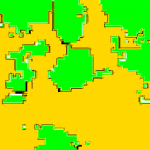

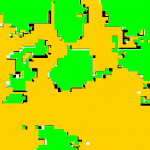

So far our approach has been to eliminate as many of an image’s features as possible except for edges and test to see if it still gets filtered. We also decided to take the opposite approach, eliminating edges by blurring them while keeping other features untouched. We proportionally resized each image such that its smallest dimension(s) is/are 200 pixels (see the “Resizing” section for why we resized this way). Then we applied a normalized box filter to blur the image, increasing the kernel size until the image is sufficiently blurred to evade filtering.

5 px

|

3 px

|

4 px

|

4 px

|

2 px

|

3 px

|

1 px

|

6 px

|

4 px

|

5 px

|

4 px

|

6 px

|

7 px

|

5 px

|

6 px

|

Table 33: The largest normalized box filter kernel size that can be applied to each image while still being filtered.

In general, we saw that WeChat’s filter was not robust to blurring (see Table 33). Non-photographic images were generally the easiest to evade filtering by blurring, possibly because they generally have sharper and more well-defined edges.

In this section we have demonstrated evidence that edges are important image features in WeChat’s filtering algorithm. Nevertheless, it remains unclear exactly how WeChat builds image fingerprints. Some possibilities are that it specifically uses filtering methods such as Sobel filtering, although a detection algorithm such as Canny edge detection seems unlikely as it does not preserve the sign of the edges. Another possibility is that it fingerprints images in the frequency domain, where small changes to distinct edges can often have effect the values of a large number of multiple frequencies, and where large changes to the overall brightness of an image can significantly affect the values of only a small number of frequencies.

Resizing

Up until this point, we have been mostly concerned with experimenting with images that have the same aspect ratios. In this section we test how changing images’ sizes affected WeChat’s ability to recognize them. How does WeChat’s filter compare images that might be an upscaled or downscaled version of that on the blacklist? For instance, does WeChat normalize the dimensions of uploaded images to a canonical size? (See Table 34)

| Original | Both (100×100) | Width (100) | Height (100) | Largest (100) | Smallest (100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200×400 | 100×100 | 100×200 | 50×100 | 50×100 | 100×200 |

| 400×200 | 100×100 | 100×50 | 100×200 | 100×50 | 200×100 |

Table 34: Examples of how two images would be resized according to five different hypotheses.

To answer these questions, we decided to test five different hypotheses:

- Images are proportionally resized such that their width is some value such as 100.

- Images are proportionally resized such that their height is some value such as 100.

- Images are proportionally resized such that their largest dimension is some value such as 100.

- Images are proportionally resized such that their smallest dimension is some value such as 100.

- Both dimensions are resized according to two parameters to some fixed size and proportion such as 100×100.